Issue 30: Fall 2020

In This Issue

When the Conversation Stops: Logopenic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia

Ask an Expert: Is Logopenic PPA an FTD Disorder or Alzheimer’s Disease?

PPA Subtyping: Helping or Hindering the Understanding of PPA?

From a Caregiver’s Perspective: Music Therapy and Language Retention

From a Caregiver’s Perspective: The Importance of Speech and Language Therapy in PPA

Download PDF version of Issue 30

When the Conversation Stops: Logopenic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a neurodegenerative disease that affects the parts of the brain responsible for speech and language, resulting in the gradual loss of the ability to speak, read, write, or understand what others are saying. Researchers divide PPA into three subtypes, including logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA), which is mainly characterized by difficulty with word-finding, resulting in frequent pauses while speaking. People with lvPPA, however, generally recall the meanings of words, unlike other types of PPA. While knowing the differences between PPA subtypes can be scientifically valuable, families living with PPA are better served receiving support and advice for the road ahead. The case of Tami W. demonstrates how ongoing engagement with knowledgeable professionals can help persons diagnosed with PPA and their care partners adapt to symptoms as they progress, as well as teach them how to cope with related challenges and identify means of support.

The Case of Tami W.

Tami W. works at a sports management firm in a major U.S. city, where she is one of its top agents. Never at a loss for words, she is known for her outgoing personality, witty banter, and unique ability to connect with the athletes she represents. But in her early 50s, she began having trouble speaking. Once praised for her knack for speaking off the cuff, even in front of large crowds, she now struggled with finding the right words, resulting in long, awkward pauses in conversations with clients. In public and especially at work, Tami felt increasingly uncomfortable and embarrassed with her language struggles.

While home for the holidays, Tami’s 24-year-old daughter Devon noticed that her mother was speaking with unusual hesitance and frequent mid-sentence pauses, as if she could not find the right word to say next. Devon, a recent college graduate who lives four hours away, did not recall her mom having such difficulties when she visited last year. Devon also realized that Tami, who recently turned 52, had stopped calling her on the phone in recent months, instead choosing to hold conversations via text—were her new language difficulties to blame? When she asked her mom if she was having trouble thinking of the right words during conversation, Tami acknowledged that she had, and that she worried that her problems could affect her job.

Together, Devon and Tami did some research online, which further concerned them. They asked Tami’s partner, Jessie, if she had noticed anything. Jessie was tentative at first—she knew how proud Tami was of her public speaking ability—but soon acknowledged that Tami had seemed less confident in her speech lately, and was at times unable to produce words, instead using placeholders like “thing” or “whatchamacallit” to refer to objects. Tami was not surprised to hear this; she had been worried that Jessie was aware of her recent language difficulties. All three decided that a doctor’s visit was in order.

Devon and Jessie accompanied Tami to her appointment. After some routine tests, her primary care

physician attributed the her language changes to job-related stress coupled with increased anxiety due to menopause. The doctor prescribed an SSRI to help Tami cope with her symptoms, and scheduled a six-month follow-up appointment. While Tami felt her symptoms were caused by more than just stress, she decided to try the medication anyway.

Searching for Answers

Several months went by, and Tami’s language difficulties did not wane. The medicine seemed to make no difference. She felt growing anxiety in her job, which is heavily language-dependent; she feared that co-workers and clients could notice her struggling to find words during meetings. Her conversational skills had long been an asset and a strength—now that talking was becoming harder, Tami experienced feelings of worthlessness, a sense of disconnect from her work, and depression.

Devon, who had started visiting more frequently, noticed her mother’s condition was worsening. Her inability to remember words mid-sentence grounded conversations to a halt, and she had begun responding to questions with “yes” when she meant “no,” and vice versa. Devon knew this was more than stress. Determined to find answers, she decided to seek a second and more specialized opinion. After extensive research, she contacted an institution that uses a multi-disciplinary approach to care, offering a more robust care team to provide her mother the most accurate diagnosis and personalized care.

At her first visit to the center, which occurred approximately two years after the onset of language difficulties, Tami underwent a series of evaluations, including a neuropsychological assessment and an evaluation with a behavioral neurologist. Imaging, blood tests and a detailed medical history were taken to help “rule in” and “rule out” different causes of her language deficits. Neuropsychological testing revealed relatively isolated deficits in language, but preservation of other thinking skills, such as memory. The neurologist found no evidence of stroke, tumor, vitamin deficiency or other potentially reversible causes of her language challenges.

This information, in concert with the family’s description of gradual, progressive loss of language, led her neurologist to make a clinical diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia (PPA). PPA is a syndrome caused by a neurodegenerative disease that currently has no cure. Tami’s language challenges were most consistent with a subtype of PPA called logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA, also known as PPA-L). More specifically, people with lvPPA have difficulty recalling the names of objects and/or thinking of words in conversation, but still understand what those words mean. Persons diagnosed with any PPA subtype can expect to continue losing language skills; because the disease is progressive, it will eventually spread beyond the language areas of the brain, resulting in further changes in cognition and even behavior. Nevertheless, Tami’s diagnosis gave her relief: Finally, a concrete reason for her language struggles.

Establishing a Care Plan

Tami next met with a speech-language pathologist (SLP). However, the SLP, more familiar with stroke aphasia, was uncertain how to help someone with Tami’s condition, so she identified a colleague who was part of a speech and language therapy clinical trial for individuals living with PPA. The trial aimed to identify and understand which communication strategies successfully capitalize on—and compensate for—the remaining language abilities of a person with PPA. It included persons diagnosed with PPA and their care partners, recognizing that communication involves a speaker and a listener—and both would need to learn new communication techniques. After careful consideration, Tami and Jessie agreed to join the trial.

The family was also referred to a local social worker for an in-depth psychosocial assessment, which included an analysis of Tami’s living situation and support networks, as well as the ways that she, Jessie and Devon were adapting to Tami’s changing language abilities and overall functioning. Devon, worrying that her presence at home may become overbearing (and beginning to feel the pressure of putting her own career on hold to care for her mother), said she had limited her visits to every other weekend. Meanwhile, Tami and Jessie told the social worker about the strain that PPA was putting on their relationship. Jessie felt frustrated by Tami’s increased dependency; for example, she had become her partner’s crutch in social situations. And both grieved the loss of the way their relationship used to be. Their emotional and intimate bond was noticeably dwindling along with their ability to maintain fluid, back-and-forth conversations.

The social worker answered the questions Jessie and Devon had about PPA symptoms, and told them to visit AFTD’s website for more information. She also referred them to legal counsel to secure Powers of Attorney for healthcare, finances and estate planning; and connected them to online PPA and FTD support groups to help them navigate Tami’s diagnosis and treatment. Being introduced to this wealth of information helped Jessie and Devon cope. Tami, meanwhile, met with her own monthly online support group for persons diagnosed, fostering a sense of community with others living with the same rare disease.

Stepping Away from Work—and Toward a New Purpose

On the advice of her social worker, Tami shared her PPA diagnosis with her boss at work, who agreed that she could and should continue her work as normal. While her language ability was an issue, she had not lost the other skills—notably her ability to relate to others—that had contributed to her storied success. But over the next year, Tami noticed that exhaustion would set in each workday around noon, making it even harder to find the right words while speaking. Her boss, concerned that she may begin losing clients, eventually asked her to step down from her position and assume a part-time administrative role at the agency. While this worked out at first, Tami’s language decline soon extended to reading and writing, making administrative work impossible, and she left the agency.

Tami applied for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)—her social worker told her that PPA is a qualifying condition under Compassionate Allowances—but her initial application was denied. She appealed the decision, and her neurologist wrote a strong letter on her behalf, clearly stating the neurodegenerative nature of PPA and the underlying diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or FTD. The appeal succeeded; SSDI benefits were instated and made retroactive to her first application.

Tami has been able to maintain a sense of purpose in her life, allowing her to manage the grief of her diagnosis. Since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, she has continued to meet with the speech-language pathologist virtually, helping to improve her quality of life. Inspired by her daughter’s persistence in finding an accurate diagnosis—and hoping to find meaning in the years she has left—Tami volunteered with AFTD and was eventually asked to join the AFTD Persons with FTD Advisory Council, a committee of persons living with a diagnosis who advise the staff and Board and raise awareness of the disease. She has also felt empowered through her work to advance research; after a conversation with her doctor, Tami decided to join an observational research program with eventual brain donation in hopes of helping researchers advance treatments and a cure. Through her volunteer advocacy work and participation in research, Tami has been able to not only feel a sense of personal accomplishment, but also a sense of hope in using her experience to help others in their FTD journeys.

Questions for discussion:

1. How did Tami’s insight into her condition contribute to getting a diagnosis and her management of the disease?

Unlike in other forms of FTD, people living with PPA often retain the ability to recognize that they are changing, and can exhibit awareness or concern for the effect their symptoms have on those around them. Tami, for example, was fully aware of what was happening to her. She joined her spouse and daughter in researching her symptoms online and fully participated in doctor’s appointments; later she helped to develop and facilitate her own care plan. Additionally, her self-awareness allowed her to attend and participate in a support group for persons diagnosed. The group helped Tami gain a sense of community and understanding by relating to others living with a rare, debilitating disease.

2. After Tami’s diagnosis, what approach did she take to seeking help?

Tami initially met with a speech-language pathologist (SLP); however, the SLP, more familiar with stroke aphasia, was not sure how to help someone with her condition, so she identified a colleague who was part of a speech and language therapy clinical trial for people living with PPA. The intervention program included both Tami and her partner Jessie, recognizing that communication involves a speaker and a listener—and both would need to learn new communication techniques. After careful consideration, Tami and Jessie agreed to join the trial and participate in its targeted language therapies, which were adjusted as Tami’s condition progressed. Throughout, they referred to the Winter 2016 issue of AFTD’s Partners in FTD Care for more information about maximizing communication success with speech and language therapy in PPA.

3. What role did support groups play in Tami’s PPA journey?

Support groups helped Tami and her family navigate the PPA diagnosis. Tami attended a support group specifically for people living with PPA, where she formed connections with others facing this diagnosis and learned coping skills. Jesse attended a group for caregivers, and Devon joined AFTD’s Facebook group for young adults. Groups that focus more broadly on FTD and Alzheimer’s provide peer support and care management strategies, and may help families become aware of and prepare for behavioral and cognitive symptoms that may appear over time.

Ask an Expert: Is Logopenic PPA an FTD Disorder or Alzheimer’s Disease?

by Emily Rogalski, PhD

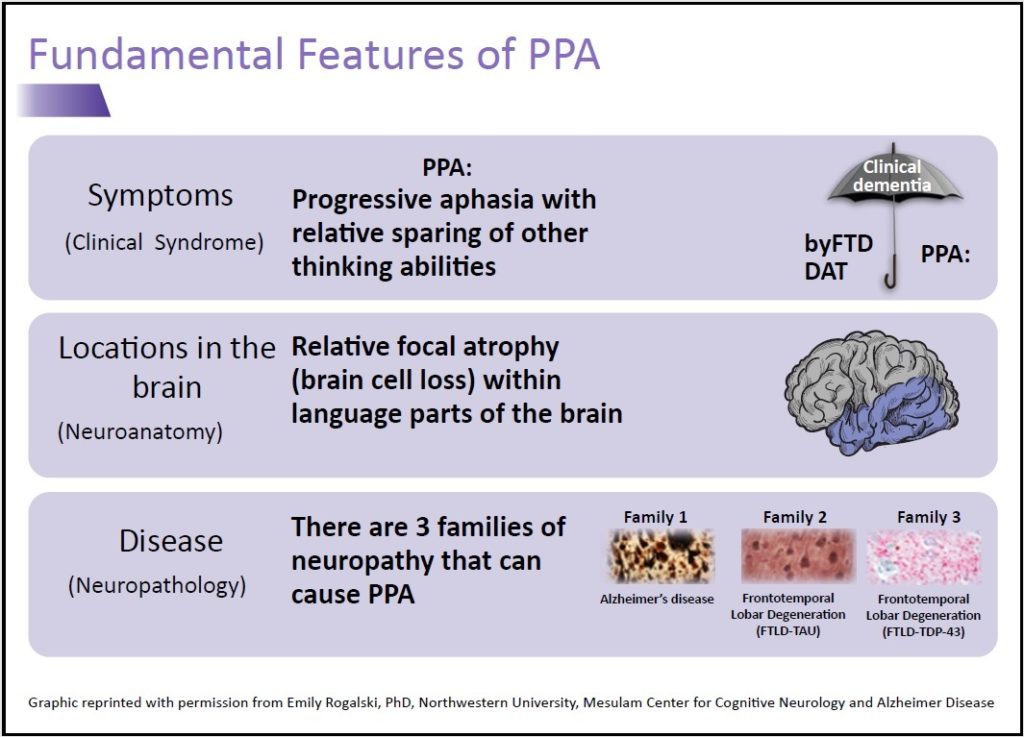

One of the biggest challenges with PPA is understanding which type of neuropathology is causing a person’s symptoms: a form of FTD or Alzheimer’s disease (AD)? One reason for this challenge is there is no one-to-one correspondence between the symptoms one experiences and the type of pathology. A neurodegenerative disorder whose primary feature is language impairment, PPA occurs when abnormal proteins implicated in AD or FTD attack the language areas of the brain. Of the three PPA subtypes, logopenic variant (lvPPA) is most commonly—but not always—associated with AD pathology, which is characterized by the accumulation of two abnormal proteins: amyloid and misfolded tau proteins in brain cells.

One of the biggest challenges with PPA is understanding which type of neuropathology is causing a person’s symptoms: a form of FTD or Alzheimer’s disease (AD)? One reason for this challenge is there is no one-to-one correspondence between the symptoms one experiences and the type of pathology. A neurodegenerative disorder whose primary feature is language impairment, PPA occurs when abnormal proteins implicated in AD or FTD attack the language areas of the brain. Of the three PPA subtypes, logopenic variant (lvPPA) is most commonly—but not always—associated with AD pathology, which is characterized by the accumulation of two abnormal proteins: amyloid and misfolded tau proteins in brain cells.

Knowing the underlying neuropathology causing an individual’s symptoms is important so clinicians can identify appropriate clinical drug trials and eventually, effective treatments (when they become available). Currently, knowing one’s clinical PPA subtype is insufficient for determining the underlying neuropathology causing symptoms. Emerging biomarkers including cerebrospinal fluid, amyloid PET scans and tau PET scans are being developed, which can help determine underlying neuropathology in living individuals. For now, true neuropathologic diagnosis can only be confirmed by autopsy.

Each diagnosis is accompanied by two labels: one that describes the clinical symptoms (e.g., PPA, a concise way to describe the language loss one is experiencing), and one that describes the type of

proteins implicated in causing the symptoms (e.g. AD). It is important to differentiate the terms “Alzheimer’s dementia” (a label that describes the symptoms of progressive memory loss) and “Alzheimer’s disease” (the name of the neuropathological abnormal plaques and tangles seen in the brain under the microscope after death).

Families of someone with a diagnosis of PPA during life may become confused when autopsy shows AD neuropathology. Is this a misdiagnosis? No—their loved one had the clinical symptoms of PPA (e.g. language loss), and these symptoms were caused by AD neuropathology (e.g. abnormal plaques and tangles).

Disease progression is another potential source of confusion. Neurodegenerative diseases do not stay in one location of the brain—they spread. The speed and direction of that spread is incompletely understood and variable from person to person, but is being actively studied. As the disease spreads, individuals will experience new and more severe symptoms. For some, the disease spreads to the regions of the brain that control memory; for others, the disease may spread to the frontal lobes and result in changes in personality, attention or judgment. Persons diagnosed and their families may be under the impression that PPA predominately impacts language, so the occurrence of memory loss or behavioral symptoms can cause confusion and frustration. Families can work with their clinicians, including social workers, who can help them navigate these changes.

Support groups may also be an important resource for families living with a diagnosis of PPA. Talking about PPA with others who understand the lived experience of the disease—both persons diagnosed and their loved ones—can present opportunities to learn coping strategies. While groups specifically focused on PPA can foster connections within a rare-disease community, groups focused more broadly on FTD and Alzheimer’s may also help families become aware of and prepare for behavioral and cognitive symptoms that may appear over time.

PPA and Depression

People with PPA experience progressive language loss, but often retain memory, personality, reasoning, and insight into their condition until the advanced stages (Mesulam, 2001; Banks SJ, Weintraub S. 2009). Engaging socially and participating in language-focused activities becomes more challenging because of their difficulties with word-finding. Combined with the awareness of their condition, those living with PPA often feel withdrawn, isolated, and excluded. Indeed, studies have shown that people with PPA are at a greater risk of experiencing depression (Medina and Weintraub, 2007).

In one study of persons diagnosed with PPA, a significant portion evaluated for depression scored in the clinically depressed range. More specifically, this study found that the number of depressive symptoms correlated with the severity of language impairments. The most common depressive symptoms included social withdrawal, lack of mental and physical energy, agitation, restlessness, sad mood and a pessimistic outlook. The study also found that people with previous depression were more vulnerable to a recurrence of symptoms because of their diagnosis (Medina and Weintraub, 2007).

Another study that compared neuropsychiatric features of PPA with cognitively normal controls suggested that PPA is associated with depression, apathy, agitation, anxiety, appetite change, and irritation. Depression symptoms are either an emotional reaction to language impairment or a noncognitive manifestation of the neurodegenerative process, the study speculated (Fatemi, 2011).

Knowing that reduced language function and a preserved understanding of their condition can leave people with PPA vulnerable for depression, the medical community must remain thoughtful and persistent in evaluating persons diagnosed for changes in mood. Attention should be given to emotional needs that are more difficult to express due to language loss. Early detection of depressive symptoms is important to ensure the most adequate treatment.

Until we have effective treatments for PPA, healthcare professionals should focus on helping those affected maintain their best quality of life. Treating depression to help improve one’s mood can impact quality of life for both people with PPA and their families. Talk therapy may help, but its utility as a treatment is increasingly limited as one’s PPA progresses, so non-verbal therapies such as music, art, dance and mindfulness can be considered as alternative mood interventions. Encouraging families to speak with their neurologist about their loved one’s changes in mood will ensure they find the best treatment options available.

References:

- Banks SJ, Weintraub S. Generalized and symptom-specific insight in behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009; 21:299–306.

- Fatemi et al. Neuropsychiatric aspects of primary progressive aphasia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011; 23:2.

- Medina J, Weintraub S. Depression in primary progressive aphasia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007; 20:153–160.

- Mesulam MM. Primary Progressive Aphasia. Annals of Neurology. 2001; 49 (4):425-32.

PPA Subtyping: Helping or Hindering the Understanding of PPA?

by Emily Rogalski, PhD

One of the most confusing topics for PPA caregivers, clinicians, and researchers studying the condition has been the nomenclature associated with it. PPA subtyping—delineated as agrammatic, semantic, and logopenic subtypes—vary in clinical features and tend to have different patterns of brain atrophy, as well as different probabilistic relationships with underlying pathology. These subtypes were developed for research purposes, and were thus incompletely validated before making their way into clinical discussions.

On the positive side, subtyping gives families a shorthand way to describe the constellation of

symptoms a person with PPA is experiencing. But admittedly, there are challenges with the current diagnostic system. Research suggests that up to 30% of individuals with PPA do not meet criteria for any of the three subtypes at the time of diagnosis. Since PPA is progressive—meaning symptoms get worse and change over time—it can also be difficult to subtype later in the disease course. And practitioners with limited specialist experience in PPA can find it difficult to diagnose the condition itself, let alone discern a subtype.

Is there an alternative to subtyping? What if a person with PPA does not meet criteria for a subtype? Neuropsychologists and speech-language pathologists with PPA expertise can provide detailed assessments of the challenges and relative strengths that the individual is experiencing. This information establishes expectations for which everyday activities may or may not be challenging for those with PPA, and can also contribute to an individualized care plan.

PPA has gotten more attention in the scientific literature in recent decades, with substantial progress being made in our understanding of the syndrome and the connections between its symptomatology, progression, pathology, and genetic implications. But many hurdles remain, particularly in terms of ensuring that people with PPA and their care partners and caregivers receive optimal information and support at diagnosis, as well as appropriate treatments, interventions and/or management strategies throughout their PPA journey.

Despite the murkiness of PPA subtyping, clinical researchers have found value in such nomenclature. But for families living with PPA, value lies not in overeducating them about their PPA subtype, but rather in anticipating their needs and equipping them with the support and information necessary to ensure the best quality of life for the road ahead. Such supports include educating them about optimizing communication to ensure the best quality of life, the role of dynamic clinical decision making in the face of declining language and other cognitive and behavioral functions, as well as emerging treatment and/or research options.

From a Caregiver’s Perspective: Music Therapy and Language Retention

by Gary Eilrich

Soon after retiring, I noticed my wife was having trouble expressing herself. Our primary care physician suggested an appointment with a behavioral neurologist, and after an evaluation and neuropsychological testing, she was diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia.

She soon began attending speech therapy sessions, which she enjoyed; she was diligent about practicing her speech exercises at home. She also enjoyed and benefited from a weekly group meeting called “Speak Easy,” which provided unique and innovative programing for people with neurogenic communication disorders. She attended the group most Mondays for two years; when she stopped enjoying the exercises, a speech language pathologist suggested music therapy to continue to preserve communication.

Music therapy involves an evidence-based, clinical use of musical interventions to improve clients’ quality of life, and, in our case, to preserve language and communication. Always a music lover, my wife was motivated to try the therapy.

The music therapist came to our home to provide private sessions, in which I also participated so I could learn more about ways to support our communication and to know what my wife needed to practice during the week. The therapist kept meticulous notes to track my wife’s progress. We learned that even though my wife was rapidly losing her ability to talk, she could still sing certain phrases, so the therapist taught her how to incorporate specific sayings into familiar songs. She learned to sing “I have to go to the bathroom,” “I love you,” and “The tilapia was good.” (Tilapia is her favorite food.)

We spend winters in another part of the country and found another music therapist there. That therapist made a CD of phrases that she and my wife worked on so we could listen and practice on long drives. Over time, my wife’s ability to express herself declined even further, but she remained able to sing the short phrases she had learned in speech therapy for longer than expected.

Music therapy provided an effective way for my wife and me to communicate even as her ability to verbally express herself declined. Most importantly, she enjoyed herself, which helped to improve her quality of life.

From a Caregiver’s Perspective: The Importance of Speech and Language Therapy in PPA

by Barb Murphy

For people living with PPA, speech and language therapy can help slow the decline of language ability and compensate for losses over time. For my husband Gary, diagnosed with PPA five years ago, speech and language therapy has had a tremendous impact. Our decision to participate in Northwestern University’s Communication Bridge Clinical Trial gave him critical word-finding and language retention skills and helped to boost his confidence when communicating.

An internet-based, speech and language therapy intervention, the Communication Bridge Clinical Trial seeks to evaluate the effectiveness of various therapies for adults with mild PPA by applying evidence-based language interventions. The 12-month program was a positive and rewarding experience, providing daily exercises to improve Gary’s language abilities, as well as invaluable weekly one-on-one sessions with a trained speech-language pathologist.

Gary initially put up a fight—he said the disease was just going to worsen and nothing could change that. But eventually he agreed to participate in the program, and he’s glad he did. The program’s person-centered approach encourages speech-language pathologists to meet persons diagnosed at their current skill set and work towards communication goals most important to them. When we started, Gary and I were told to list words that we felt were important for him to retain, and to practice those words daily. He even practiced on vacation! Now, six months since our final session, Gary is still able to recall all but the eight most difficult words on that list.

In addition to the language exercises, I found that working with a speech-language pathologist also helped me to both better understand PPA and find ways to advance Gary’s treatment. The entire team we worked with, in fact, was dedicated, patient, and encouraging. They taught my husband countless ways to search for words—skills that still help him today, almost five years since his diagnosis.

While my own participation in the program was limited— I was the cheerleader behind my husband, encouraging him when he needed it—I enjoyed seeing his dedication to practicing each day. The program’s structure allowed him to track his progress, which motivated him. The skills he learned gave him the confidence to pick up the phone and call his buddies and sons for the first time since his diagnosis. For that, we are very grateful.

We have set two goals for our PPA journey: to retain for as long as possible Gary’s speech and word finding—in whatever form they take; and to help others facing PPA who could benefit from this type of program. We do feel the program was helpful in our journey, and if our participation can advance research and help Gary retain those 75 words, then I am especially glad we participated.

To learn more about participating in the Communication Bridge Clinical Trial, please visit the Featured Studies section at theaftd.org.