Creating Well-Being with Person-Centered FTD Care

Partners in FTD Care, Summer 2021

Download the full issue (pdf)

By Mary O’Hara, LCSW

José G., the subject of this issue’s case study, had a rich social and family life, full of accomplishment and connection. But soon after his diagnosis, he lost his job, his elected appointment, his car, his hobbies, his financial independence, and many of his relationships. Consequently, José lost his sense of identity, control, meaning, and purpose. Due to understandable concerns about his abilities, safety, and judgment, many of the things most important to José were taken away.

Because of FTD’s unpredictable symptoms, family or paid caregivers may naturally focus on minimizing the impact of new behaviors and compensating for new impairments to keep the person diagnosed safe. Safety, however, does not necessarily have to come at the expense of maintaining engagement, connection, and meaning in their life.

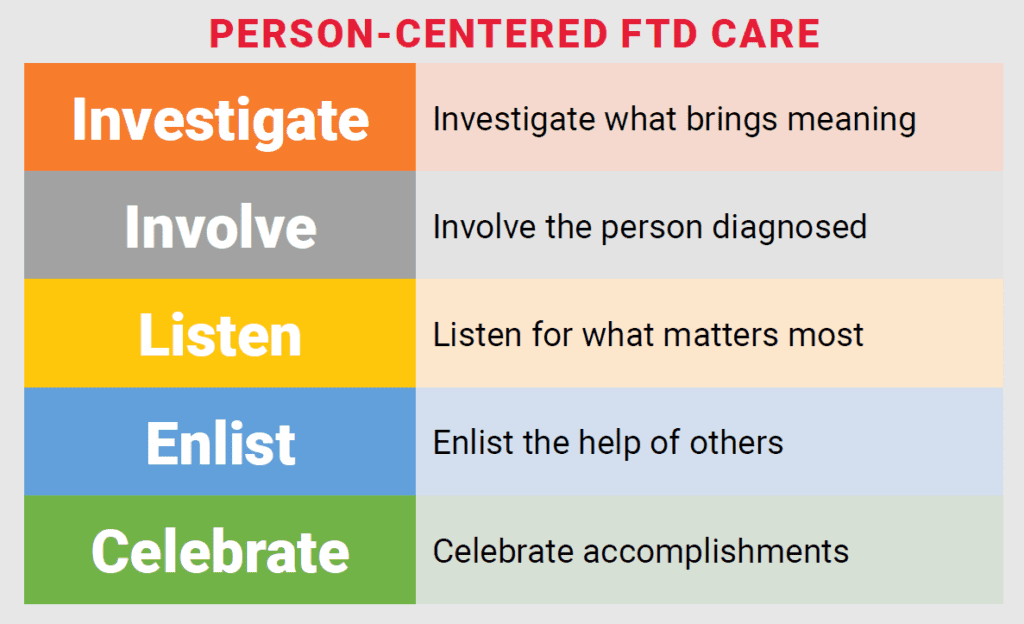

Person-centered FTD care should focus on what is still possible for the individual diagnosed. Doing so can mitigate some of the shame and social stigma often associated with a diagnosis: Seeing a person with FTD for what they can still do enables families, care providers, and communities to be more supportive and welcoming. Defining a person with FTD by what they have lost due to their disease risks marginalizing, stigmatizing, and isolating them further.

The PERMA model of well-being, designed by the psychologist Dr. Martin Seligman, is applicable here. (PERMA stands for Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.) Dr. Seligman designed PERMA to help shift one’s thinking from a loss model, focusing on what is taken away, to a more positive model aimed at what one can “bring in.” While not developed for dementia, PERMA can be adapted to help family and professional caregivers see what remains possible in the life of a person with FTD, and how they can introduce greater engagement, connection, or meaning.

Positive Emotions: Identify what brings out the most positive emotions and experiences for the person. Even if José could no longer waterski or drive the boat, he might still look forward to spending a day with others out on the water. This concept also prioritizes monitoring, addressing, and treating changes in mood. For José, art therapy could be a fulfilling way to express his emotions.

Engagement: Engagement involves finding activities that both challenge the person diagnosed and are suitable for their cognitive abilities, while also maintaining safety. José’s daily walks with his fellow churchgoers kept him safely engaged outside of the house while also minimizing the risk of him overeating if he were left home alone all day.

Relationships: FTD can be a very isolating experience, and may cause some friends to fall away due to their discomfort with it. But if they learn how to respond to FTD’s symptoms, they may be more likely to adapt and stay connected. Many newly diagnosed individuals can also form new relationships by connecting with others living with a diagnosis, whether online or in person.

Meaning: While it is impossible to fully replace the meaning derived from a former job or newly inaccessible hobby, new, different sources of meaning can be found. For example, José may find meaning by spending time with his former colleagues, volunteering in an appropriate capacity at his church, or tending a community garden. Understanding what the person diagnosed most values can help to re-establish sources of meaning intheir lives.

Accomplishment: Working on or finishing a task, no matter the size, can lead to feelings of accomplishment. Even daily routines provide regular opportunities for small but meaningful accomplishments. José might feel accomplished by returning to running with a friend.

Applying the PERMA model to create well-being with a person diagnosed cannot be accomplished by care partners and caregivers alone. They need support—from their family, friends, community, and the health system. The person diagnosed may resist attempts to introduce new activities or routines. Deciding how much to push and when to back off can be challenging for caregivers. Families therefore need help from their support system in introducing these concepts. While the PERMA approach asks more of our communities, it also offers much more to a person living with a new diagnosis—and can offer family members greater support by reducing distress, worry, and much of the guilt associated with FTD caregiving.

See also:

By Category

Our Newsletters

Stay Informed

Sign up now and stay on top of the latest with our newsletter, event alerts, and more…